Insights | 18 November 2024

OECD Pillar Two tax disputes: an introduction

With the end of the tax year approaching in many jurisdictions, multinationals will be assessing how the OECD’s “Pillar Two” tax system will affect their businesses.

2024 is the first year in which several jurisdictions – including the UK, Cyprus, France, Germany, Ireland and the Netherlands – will implement parts of the Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules (the “GloBE Rules”).

While these may give rise to disputes between taxpayers and State authorities, investor-state arbitration may be an option for multinationals seeking legal redress.

Update: The U.S., to date, has not implemented Pillar Two. While the Biden administration supported Pillar Two, in a 20 January 2025 executive order, the Trump administration confirmed that any commitments made by the Biden administration with regard to the Global Tax Deal have no effect within the U.S. absent an act of Congress.

Although this is more of a statement of fact than policy, the executive order also directs the Secretary of Treasury to investigate whether any foreign countries are not in compliance with a U.S. tax treaty or have (or are likely to have) tax rules in place that are extraterritorial or disproportionately affect U.S. companies; if so, it may propose retaliatory measures. [1]

A second executive order issued on the same day directs officials to investigate trade matters, including whether any foreign countries are subjecting U.S. citizens or companies to discriminatory or extraterritorial taxes pursuant to section 891 of title 26, United States Code.[2] This provision allows the U.S. Government to double its tax rates on certain foreign citizens and companies whenever the President finds that, in those foreign countries, U.S. citizens and corporations are being subjected to discriminatory or extraterritorial taxes.

It remains to be seen how these executive orders will impact the Pillar Two reforms and whether, in the face of retaliatory U.S.-imposed trade tariffs and taxes, countries currently applying the GloBE Rules will reverse course, press on undeterred, or raise the stakes – for example by applying “digital services taxes” on U.S. tech companies.

GloBE Rules are likely to increase taxpayer-State disputes

Large multinational businesses will already be familiar with the GloBE Rules, which aim to ensure that multinational groups with a consolidated annual revenue of over €750 million pay a minimum effective tax rate (“ETR”) of 15 per cent.

Although complex, broadly speaking, the GloBE Rules seek to achieve the minimum 15 per cent ETR by encouraging a critical mass of States to implement two interlocking rules in their domestic tax legislation:

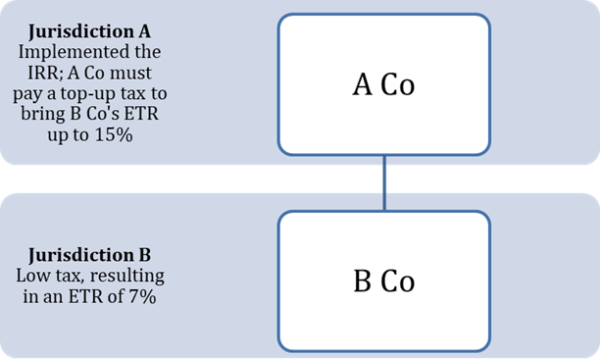

- The Income Inclusion Rule (“IIR”): this seeks to apply a top-up tax to parent entities of subsidiaries whose ETR is below 15 per cent. If the parent entity is in a jurisdiction that has implemented the IRR, it may be liable to pay the top-up tax to bring the ETR of the subsidiary up to 15 per cent.

In the following example, the application of the IRR would result in A Co (the parent) paying a top-up tax on profits generated by B Co (its subsidiary):

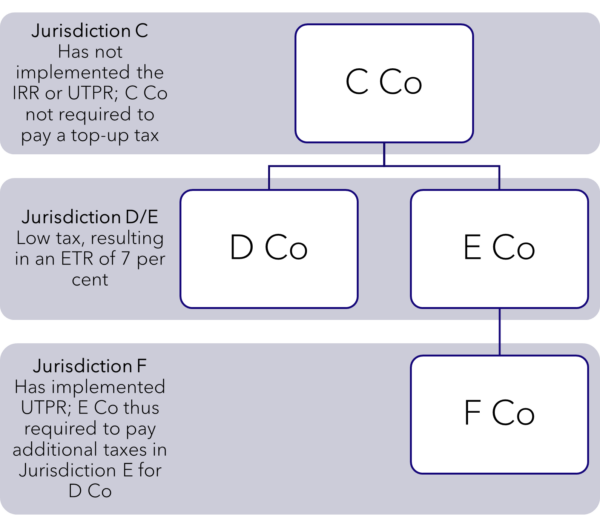

- The Undertaxed Profits Rule (“UTPR”): the UTPR is intended as a backstop where a low-tax entity’s profits cannot be taxed via the parent company because the latter’s jurisdiction has not implemented the IRR. It does this by taxing the undertaxed profits via another entity (or multiple other entities) in the group. Where there are multiple jurisdictions that could apply the UTPR, the additional tax is allocated between jurisdictions based on a ratio of employee headcount and net tangible assets located in each jurisdiction.

The GloBE Rules envisage that the UTPR can be implemented by denying those entities tax-deductible expenses, so as to increase their overall tax liability to recover the undertaxed profits of their affiliate. However, the Rules also provide that the UTPR can take any form of adjustment with an equivalent effect, including (potentially) a direct additional tax levy.

The following situation shows how the UTPR could operate, resulting in E Co facing an additional tax burden in the amount of the undertaxed profits generated by D Co:

The GloBE Rules are a set of model rules, providing States with a template to implement in their domestic legislation. How exactly the Rules will apply for a given multinational group will, therefore, depend on how they are implemented in any given jurisdiction. There are also caveats and exceptions to these broad principles within the framework (e.g., safe harbour and penalty relief provisions, giving transitional relief during the initial years of implementation of the Rules).

In other words, each multinational’s situation will be fact-specific. Nevertheless, it appears inevitable that the implementation of the GloBE Rules will give rise to disputes between taxpayers and States, including the following:

- disputes over the correct application in the domestic law of the IRR or UTPR-implementing jurisdictions (“application disputes”);

- Disputes arising out of situations of double or over-taxation, caused by inconsistent implementation or application of the GloBE Rules between jurisdictions (“double-taxation disputes”); and

- disputes over whether implementing rules, or their application, comply with States’ obligations to foreign investors under international investment treaties or agreements (“investment disputes”).

Dispute resolution mechanisms available to taxpayers

Depending on the dispute, different dispute resolution mechanisms may be available to taxpayers. In each case, taxpayers should seek expert advice to determine which option (or options) are most likely to achieve a positive outcome.

I. Domestic tax appeals or court proceedings

Given the novelty and complexity of the GloBE Rules, disagreements will inevitably arise between taxpayers and domestic tax authorities over their application.

For multinationals with profits in low-tax jurisdictions – and the parent entity located in a jurisdiction implementing the IRR – this may result in more tax application disputes in the tax administration of that parent jurisdiction.

Where the parent jurisdiction does not apply the IRR, multinationals may find themselves in disputes with one or several tax authorities applying the UTPR.

Such application disputes will be governed by the applicable domestic laws (including those implementing the GloBE Rules) in the IRR and UTPR implementing jurisdictions. They will be subject to the tax and judicial appeal mechanisms available, in the jurisdiction concerned.

In jurisdictions with sophisticated and efficient tax appeal systems, taxpayers should be hopeful of satisfactory outcomes, without too much of an additional administrative burden.

However, multinationals disputing the tax assessments of less sophisticated authorities may not be so fortunate. We address below how, in some cases, arbitration under investment treaties may offer a preferable alternative/additional forum for application disputes.

II. Arbitration mechanisms under double taxation treaties and related instruments

Taxpayers may seek resolution of double-taxation disputes via mechanisms under double taxation treaties. Such disputes might arise where several jurisdictions apply the IRR or UTPR to the same multinational group, but apply the relevant principles inconsistently.

The traditional dispute resolution mechanism under tax treaties is the Mutual Agreement Procedure (“MAP”). Where a taxpayer considers that the State has applied taxation inconsistently with the relevant tax treaty provisions, it can request that the two States party to the treaty seek a negotiated agreement with the aim of eliminating the over-taxation.[3] However, the taxpayer has no right to participate in such negotiations and no recourse if the States fail to reach an agreement.

Following the adoption of international instruments designed to encourage arbitration of double-taxation disputes (including by the OECD), some tax treaties now include optional or mandatory arbitration mechanisms.[4] These procedures typically take one of two forms:

- “last-best-offer” (so-called “baseball arbitration”), where each party submits an offer and the arbitrator(s) decide between them; or

- “binding opinion” where, after hearing the parties’ submissions, the arbitrators issue a reasoned opinion determining the dispute in accordance with the applicable law.

Within the EU, the EU Tax Dispute Resolution Directive of 10 October 2017 mandates arbitration to resolve disputes between Member States as to the application of double tax treaties, with the “binding opinion” procedure operating as the default mechanism.[5]

However, like MAP, these forms of tax treaty arbitration are still a State-to-State process, with the taxpayer largely excluded and with little, if any, control over the procedure or its outcome. And tax treaty arbitration is (necessarily) limited in scope to resolving questions of application of the double tax treaty in question.

III. Investor-state arbitration under investment treaties or stabilisation agreements

In contrast to application disputes and double-taxation disputes, which take the existence of the Pillar Two framework as a given, taxpayers may seek to challenge the Pillar Two rules themselves. Investor-State arbitration (often called “investor-State dispute settlement” or “ISDS”) may offer an attractive avenue for multinationals in this position.

Taxpayers able to avail themselves of the protections of an applicable multilateral or bilateral investment treaty could, for example, argue that legislation implementing the GloBE Rules violates the standards of protection those investment treaties grant under international law.

Such standards of protection include the “fair and equitable treatment” (“FET”) standard. States may fall foul of this where they drastically alter their regulatory framework in breach of an investor’s legitimate expectations, or where they treat investors in a grossly unfair or arbitrary manner. And the “national treatment” and “most favoured nation” standards require States to treat foreign investors at least as favourably as they would treat their own investors, or investors of third States, in like circumstances.

- Most investment treaties also prohibit the host State from expropriating investments of foreign investors without paying prompt and adequate compensation. Conceivably, a State could be deemed to be unlawfully expropriating the taxpayer’s investment, or the taxpaying subsidiary itself, if the GloBE Rules result in the imposition of a sufficiently large top-up tax.

- Investment treaties may also provide recourse for taxpayers in application disputes with host States, if the tax authority applies the GloBE Rules in an unfair or arbitrary manner, or where the taxpayer is denied the opportunity to appeal a tax assessment in accordance with applicable legal processes.

- Alternatively, multinationals may benefit from a contractual investment agreement with the host State. Investment agreements often include so-called “stabilisation clauses” (i.e., where the State provides contractual guarantees against regulatory change). Multinationals may be able to invoke such clauses against States implementing the GloBE Rules, if their application results in tax treatment falling foul of the stabilisation clause in question.

- Investment treaties or agreements usually offer foreign investors the right to initiate ISDS against the host State. In contrast to domestic tax appeals or court proceedings, ISDS has the benefit of offering investors an international, neutral forum in which to resolve the dispute with the host State, taking the dispute outside the discretion and control of the host State’s tax system or judiciary. It also differs from arbitration under tax treaties, because the taxpayer itself has standing to bring proceedings directly against the host State (unlike the State-to-State tax treaty arbitration process, where the taxpayer is excluded). Successful claimants in ISDS arbitration proceedings will receive an arbitral award that is readily enforceable in almost all countries globally, as if it were a judgment of their own courts.

In our next post, we will explore further the types of claims that may arise in ISDS proceedings relating to the implementation of Pillar Two, and any potential hurdles that claimants might need to overcome for such claims to succeed.

End notes:

[1] https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/the-organization-for-economic-co-operation-and-development-oecd-global-tax-deal-global-tax-deal/

[2] https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/america-first-trade-policy/

[3] See, for example, Article 29 of the UK-Kenya Double Taxation Treaty: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7f9d8a40f0b6230269090e/uk-kenya-dta-consolidated_-_in_force.pdf

[4] The Sample Mutual Agreement on Arbitration on the implementation of paragraph 5 of Article 25 of the OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital 2017 includes “last-best-offer” arbitration as mandatory if the competent authorities do not resolve issues between them. The OECD’s proposed multilateral convention forming part of the BEPS Framework also provides options for arbitration (last-best-offer and reasoned opinion). Article 25 (Alternative B) of the UN’s Model Tax Treaty also includes an arbitration mechanism under which either State may refer issues to binding arbitration if they remain unresolved after the MAP.

[5] Council Directive (EU) 2017/1852 of 10 October 2017 on tax dispute resolution mechanisms in the European Union [2017] OJ L 265, pp. 1–14.

Back to listing